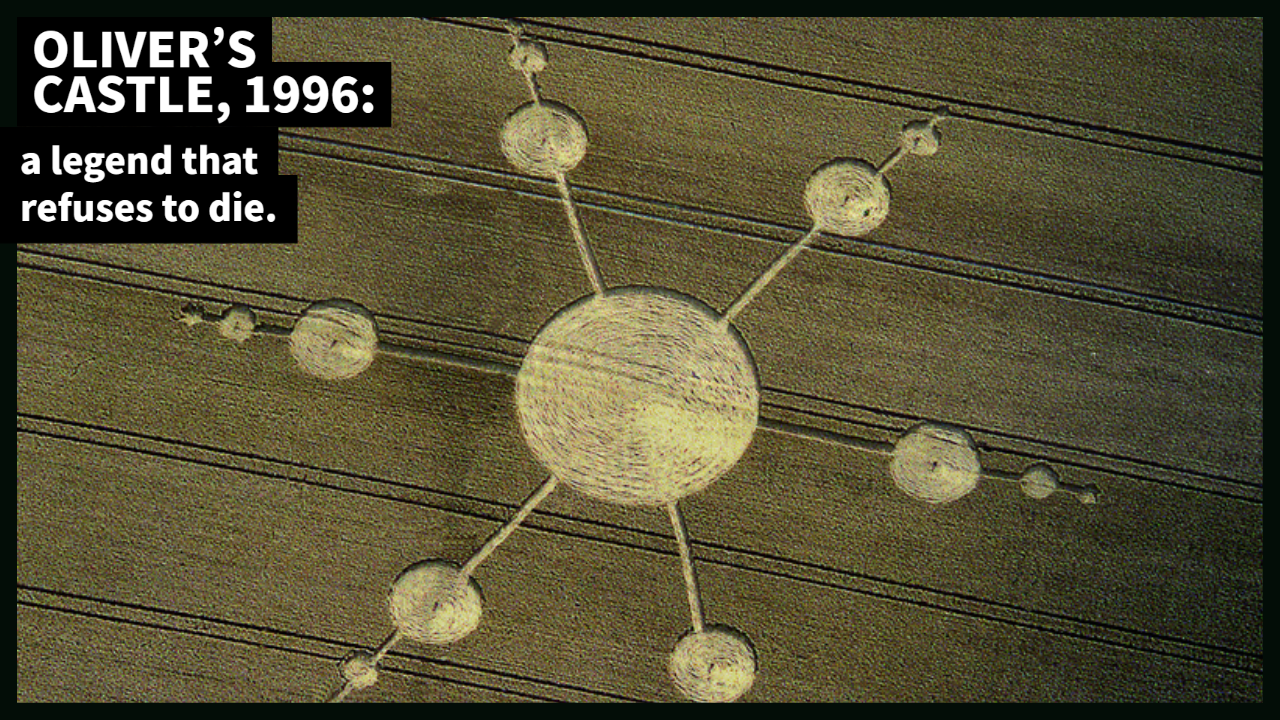

Oliver’s Castle 1996: The Video That Won’t Go Away

INTRODUCTION

On the morning of 11 August 1996 a man calling himself Jonathan Wheyleigh left telephone messages for cerealogist Colin Andrews and American film-maker and croppie Peter Soresnen at The Barge Inn. The caller outlined how he’d spent the previous night camping at the ancient Oliver’s Castle hillfort on Roundway Down above Devizes. Whilst here he had filmed dazzling balls of light spectacularly forming a crop circle in a field directly under the escarpment. Mr Wheyleigh would, he explained, turn up at the pub later in the day to share his footage.

The video recorded by Wheyleigh has become ingrained in cerealogical culture and continues to inspire debates and discussion. It is continually posted and reposted in crop circle themed outlets on social media. Those balls of light really do seem to leave a new formation — albeit a rather shaky snowflake — in the wheat underneath them. For some, the footage is clear proof of this particular circle’s paranormality, whilst others are more sceptical, viewing the entire episode as an attempt to dupe croppies with a well conceived, but ultimately flawed plan.

WHEYLEIGH'S FOOTAGE

Shortly before The Barge closed that night, Wheyleigh found his way inside. Sorensen had left an hour or so before but more than enough croppies were on hand to view the film through the black and white viewfinder on Wheyleigh’s video camera.

On 14 August Wheyleigh returned to the pub at lunchtime and introduced himself to Sorensen. The American later outlined what had happened that night on Oliver’s Castle:

[Wheyleigh] said he had left the pub and gone to spend the night at the hill fort, despite the fact that it had been raining, using only a big piece of plastic to cover his sleeping bag. Early in the morning he heard a strange noise, like the classical “electronic cricket” (a sound frequently reported in association with crop circles). The rain had already stopped, so he crawled out of his bag to see what was happening.

There, way down in the valley below the steep slope of the hill, were balls of light flying around over the crop. He watched dumbfounded for a few moments, and then grabbed his video camera out from inside the sleeping bag, where he had stashed it safe from the rain. At first it wouldn’t work because of moisture condensation. But luckily, after a few moments his camera began to function properly. By that time the lights had disappeared. But they soon reappeared, and that’s when he started shooting.

The cameraman claimed he believed his safety may be in danger if he revealed his phone number or address to anyone (presumably because the powers-that-be wouldn’t be happy with the truth about the circles’ origins coming to light), so he provided Sorensen with the telephone number of a friend who would be willing to pass on messages.

Croppie Polly Carson is open mouthed viewing the Oliver’s Castle footage.

Wheyleigh then promised Sorensen a copy of the footage together with exclusive rights to distribute the footage, eventually handing over a VHS cassette three weeks later during a meeting at The Waggon and Horses pub in Beckhampton. Also present was another film-making croppie called Lee Winterson. The latter suggested the group make their way to AVP Studios, a film-editing suite he used in Swindon where they would all be able to review the video on professional equipment. Unbeknownst to Wheyleigh, Sorensen recorded his own ‘documentary footage of our cars driving to this historic first analysis of the mysterious footage.’

DOUBTS AND DISSECTION

At the studio Sorensen and Winterson reviewed the film in slow motion and became troubled by what they saw. Most notably, the balls of light flying low above the field failed to illuminate the crop below them. Furthermore, the lights presented no motion blur, even though a slow shutter speed would have been required in the early morning light. Nonetheless, Sorensen returned to The Barge Inn and spent two evenings replaying the footage to the croppies who wished to see it first hand.

In the following days Sorensen was contacted by John Huckvale, the owner of the Swindon studio. He had conducted his own analysis of Wheyleigh’s footage and was confident it was faked; the balls of light had been added using computer animation. Sorensen explains how Huckvale had come to his conclusion:

We all know how movie film is a long strip of tiny pictures called frames. Video frames, on the other hand, are recorded on tape as electromagnetic pulses – which are invisible, so you can’t hold the tape up to the light and see the pictures. Duh.

Now, here’s the crucial technical quirk of video that you must understand to realise why the Olivers Castle tape is a fraud: Each video frame is composed of two “fields,” which are the odd numbered lines and the even numbered lines that comprise every TV picture. All the odd lines (first field) are scanned initially, and then the even lines (second field) are scanned. These fields are recorded and displayed sequentially, one after the other (1/50th of a second apart on the British, “PAL” system, which displays 25 frames per second). Each field shows the whole scene at a slightly different moment in time. THEY ARE EFFECTIVELY TWO SEPARATE FRAMES in their own right, except that they can’t be viewed separately when you pause your VCR.

When you stop a movie projector you get a single still picture. But a frame of video, composed of those two fields – two separate pictures captured an instant apart – often flickers if there’s significant motion during that time. Try pausing a shot of a football in flight, or anything moving fast, and you’ll see what I mean.

The balls of light on the original video show no such flickering when the tape is paused, despite their apparent hundred-mile-per-hour speed! This could not possibly be if they were captured with a normal video camera. This isn’t my personal opinion, this is a matter of fact. Video frames have two fields. The lights should move slightly between each of the fields. They do not!

But computer animation can produce exactly that result. In fact, computer systems have the option to render scenes with, or without, motion between the fields. But it takes longer for the computer to render with the fields properly. It also takes considerably longer to render motion blur. And time was a very important factor in this job, because Wheyleigh was committed to showing the tape at the Barge that night.

At the risk of beating a dead horse long into oblivion, consider if, instead of a video, we were dealing with motion picture film here. And what if the lights on the film were motionless for two frames, then jumped to another position in the third frame, where they again held still for two frames before jumping again, and so on. Everyone would immediately realise that something was very seriously wrong. Well, the exact same thing is afoul with the Olivers Castle tape, except the abnormality is hidden within the two overlapping fields of each video frame. If only I could hold the tape up to the light and show you the pairs of motionless fields!

So, basically, the lights had to be animated with a computer and added to the scene afterward, as was the appearance of the crop formation itself. It’s not unlike how Tom Hanks was put into the scenes with JFK in “Forrest Gump.” The [Oliver’s Castle] video is a hoax, plain and simple.

During August Sorensen contacted the telephone number Wheyleigh had provided him with. Sorensen suggested the video was a hoax. The call was not returned and a few weeks later the telephone was disconnected.

CONFRONTATION

It seemed that Sorensen was not the only researcher to have been granted exclusive rights to distribute the Oliver’s Castle footage; Colin Andrews had been spun the same line. Andrews harboured his own doubts about the video and had employed a private detective to perform some digging into the mysterious Jonathan Wheyleigh. A statement on Andrews’s website outed Wheyleigh as John Wabe, an employee at an animation and film studio in Bristol.

Rather than accept Andrews’ claims at face value, Lee Winterson decided to do further research. He telephoned film production studios in the Bristol area and was told that Wabe was employed by First Cut Studios, a supplier of ‘video post services and animation to professional media productions’.

In order to establish Wabe’s identity, Winterson and John Huckvale posed as potential clients and arranged a visit to First Cut Studios. Taking a video camera in with them, they spotted a photograph of Wabe on one of the walls. Winterson was able to verify that Jonathan Wheyleigh and John Wabe were the same individual.

John Wabe’s car: the same colour, model and registration plate as that driven by Jonathan Wheyleigh. Photograph by Peter Sorensen.

In conjunction with Japan’s NTV who were making a documentary on the Oliver’s Castle footage, Winterson and Sorensen planned a ‘sting operation’ against Wabe, hoping they would be able to extract a confession from him. Winterson writes:

On Friday, July 18th , 1997, at approximately 730 AM, Lee, Peter, and seven Nippon TV camera crew people made their way to Bristol and the First Cut Studios. The film crew went inside with cameras rolling, while Lee and Peter sat outside in a car park with communication devices, sensing every move. There was a technical problem with the communications devices, so it was difficult to ascertain what was occurring inside. However Lee was relaying to Peter the events which were taking place which was this: The business partner of John Wabe, John Lomas, was shown the footage by the TV crew and confronted about John Wabe’s connection to it. He said that “Yes, John was involved”, but that the film crew would have to talk to John Wabe personally. John Lomas left the room at this point to consult with John Wabe, relating the nature of the film crew inquiry. While the film crew was unaware, John Wabe fled out of his office, leaving a client there on the spot.

Wabe ran from the building and jumped into the same car that Wheyleigh had driven to AVP Studios from The Waggon and Horses the previous August. He waved at Sorensen as he drove away from the scene.

John Wabe later made telephone contact with Lee Winterson and, according to the latter, admitted ‘he was involved in the production’ of the video. Wabe declined to share further details due to an exclusive agreement with Discovery Channel USA.

Colin Andrews claims Nippon Television provided him with a video cassette ‘showing John Wabe confessing to fraudulently making the Oliver’s Castle video’. It seems the contents of this video have never been publicly aired. However, in National Geographic’s Paranormal? Crop Circles documentary (2005) admits to his involvement: “I just really thought it would be quite a good wheeze to see how they [croppies at The Barge] reacted when that footage was placed in front of them … and that’s what I did.’

FURTHER READING

Colin Andrews (1996): Crop Circles of 1996; http://www.cropcircleconnector.com/cpri/flashcolin1.html

Colin Andrews (1999): John Wabe Filmed Confession – Flown to CPR Offices: http://cropcircleconnector.com/CPRI/wabe99.html

Colette Dowell (1996): Oliver’s Castle Crop Circle Video Controversy; http://www.robertschoch.net/Oliver’s%20Castle%20Crop%20Circle%20Video%20Controversy%20Colette%20Dowell%20CT97.htm

Lee Winterson (1997): The Oliver’s Castle Video Controversy Exposed; http://tzone.kulichki.com/articles/video/rem.html

Peter Sorensen (1999): The Case of the Vanishing Cameraman; http://cropcircleconnector.com/Sorensen/articles/sorensen.html

Lee Winterson (1997): Inquiring Minds Need To Know; http://www.robertschoch.net/Crop%20Circle%20Video%20Oliver’s%20Castle%20Fraud%20LWCMD%20CT.htm